Dorothy Tse is the author of four short story collections in Chinese, including So Black and A Dictionary of Two Cities. Her collection, Snow and Shadow, translated by Nicky Harman, was long-listed for The University of Rochester’s 2015 Best Translated Book Award. A recipient of the Hong Kong Biennial Award for Chinese Literature and Taiwan’s Unitas New Fiction Writers’ Award, Tse is a co-founder of the Hong Kong literary magazine Fleurs de lettres. She currently teaches literature and writing at Hong Kong Baptist University.

Dorothy Tse is the author of four short story collections in Chinese, including So Black and A Dictionary of Two Cities. Her collection, Snow and Shadow, translated by Nicky Harman, was long-listed for The University of Rochester’s 2015 Best Translated Book Award. A recipient of the Hong Kong Biennial Award for Chinese Literature and Taiwan’s Unitas New Fiction Writers’ Award, Tse is a co-founder of the Hong Kong literary magazine Fleurs de lettres. She currently teaches literature and writing at Hong Kong Baptist University.

The Door

translated by Natascha Bruce

By the time the men arrived, the sky was a swathe of bruise-dark purple, a red and blue concoction that seeped through the air like melting stage make-up. I leaned from a second-floor window and spied on them as they swaggered up the main street. They wore baggy, factory-issue windbreakers that puffed in the wind, like balloons ready to take flight. But when they reached the front door, their trapped shadows leaked away, leaving them more like deflated dolls.

They did not remove their shoes, which were caked in dust and mud. Instead, they marched straight inside, treading all over my wife’s well-swept floor and throwing themselves onto the sofa, and the chairs that circled the dining table (and, in one case, onto Lily’s wooden rocking horse), asking what I had to eat. I fetched a pear tart from the kitchen and, as I sliced through it with a wheel cutter, made sure to turn and watch them. Just as expected, they were immersed in their own gloomy worlds and failed to notice my wife’s masterpiece. I couldn’t help feeling sad for her, and her meticulous efforts; of course such a refined gesture was wasted, with guests as boorish as these.

My wife had made the tart the night before, kneading flour and water into a soft skin and pressing it into a circle, then laying on slices of pear in a spiral, working out from the centre. When she put it in the oven to cook, the crust rippled like waves and the pears glistened like molten gold.

‘There aren’t many moments in life as moving as this,’ I said to her, watching the transformation through the oven door. She was standing beside me and giggled behind her hand, elbowing me in the arm as though I’d made a joke.

The men devoured the tart in an instant, scraping down to the bottom of the dish and coming face-to-face with my pathetic reflection in its stainless-steel surface. I thought back to the last time my wife made one, and felt its lingering sweetness welling in my throat. She and Lily would probably be on the train by now, far outside the city. Now only the men were in the flat, with their chewing and belching, their periodic hearty slaps at something or the other, and their constantly jiggling legs. I moved to a far corner of the living room to escape them, sitting down on a low stool near the entrance to the kitchen.

I’d never been fond of these manly get-togethers. Inviting them over had been my wife’s idea. A few days holiday were coming up, and she’d put a hand over mine and asked about my plans. I had the idea of building a model castle with Lily (I’d bought a set and hidden it away under the bed). There was also a strip light in the kitchen that hung down at one end, and it was high time I fixed it. But my wife didn’t seem to be paying attention – she went to stretch out on the sofa, closed her eyes, and let out a soft, contented sigh.

‘The thing is, I’ve bought train tickets. I’ve decided to take Lily away for a couple of days, to a faraway guesthouse, and let you have a bit of freedom. Why don’t you invite your friends round?’

And, of course, those ‘friends’ she mentioned were the men I worked with in the furniture factory, fixing and inlaying wood. I didn’t have anybody else.

*

Several years before, in order to live with my wife in the city centre, I’d had to leave the little flat that I shared with my parents in District M, where we relied on one another for everything. At the time, Lily was still inside what I used to think of as my wife’s black aquarium. I would spread my fingers across her rounded belly, and feel the faint, rippling motions of a lonely aquatic creature. Perhaps another description could have been a train without a view? When I left, watching from the train as the icy night swallowed row upon row of squeezed-together houses, I suddenly realised that I didn’t recognise a single person in the fluorescent-lit carriage. My wife and I had known each other less than six months; she was fast asleep against the darkened window-glass, and her illuminated face took on the contours of a stranger, shaking with the rhythm of the train. I placed my hand on the high swell of her stomach and tried to imagine the child’s face, but Lily didn’t have a face yet, or a name. On public transport, nothing is more permitted than feeling like a stranger. I thought I’d miss the familiar people from back home, but the train entered a tunnel and my parents’ voices were crushed by the roar of the engine. Even I changed, turning into the flickers of light and shadow projected into the carriage from outside.

Starting a new life was easier than I imagined. I brought only one suitcase and moved into the flat where my wife had been living all along. Everything was already there. Light fixtures with cloth umbrella shades hung from the ceiling, casting a golden glow over the ripe peaches on the dining table. She had crocheted antimacassars, which extended like cobwebs along the length of her sofa, and there was a thriving tropical plant, grown to the same height as me. A coat pattern she was making spread across the work table in the living room (she dreamed of becoming a fashion designer, but had been drawing up patterns for other designers ever since art school). Pulling back the sunflower-print shower curtain and soaking in the tiny bathtub, I had the feeling that I’d become another part of the house. In her orderly space, I had come alive.

But after moving into my new home, I was much farther from the furniture factory, which was on the outskirts of District M. To get to work on time, I had to wake up at the crack of dawn, when even the dust motes were still asleep, and join the flow of commuters feeding into the sea of drab city faces. And once I became a regular passenger, there ceased to be anything charming about trains. In those years, the crush of passengers was rife with resentments, especially between locals and the many others who came from elsewhere. A good number of times, a muttered comment sparked an on-board fist fight. Nothing ever went quite so far as the poison gas attacks reported in other cities, but suspected bombs turned up at the station on more than one occasion. Eventually, they were all dismissed as pranks, but there were always a couple of skulls or shoulders trampled in the preceding panic.

On days off, I chose to stay at home as much as possible. I read, or fixed furniture, or simply stayed in bed with my wife until Lily pushed through our door, clutching her book of fairytales. She’d climb up and burrow her way in between our lazy bodies, demanding that we go through those crazy stories yet again: a mother who sold her own child to support her desperate craving for cabbage; a daughter who disguised herself in animal skins to escape the lascivious affections of her father; a blue-bearded monster who killed his wives and kept the corpses locked in a secret room.

Once in a while, I’d go with my wife to meet her friends and, to my surprise, did not dislike these gatherings. My wife refused to believe that I’d never really socialised before, because her friends always showered me with praise for my impeccable manners. She didn’t know it was precisely because I had no history in those situations – I didn’t have to act like ‘myself’, so I simply played the role of her husband.

My wife didn’t have the kind of girlfriends who were always heading out to the beauty salon or comparing latest shoe styles, but all sorts of people seemed to feel especially drawn to her. The building’s cleaning lady, for example, who was always taking her aside to share pieces of neighbourhood gossip. Or the man who came to fix the water pipes, who could recognise her from miles away and would wave enthusiastic greetings, even though he’d only been around once in months. Or the solitary old lady who used to sit out on the main street in her wheelchair, taking in the sun, still as a statue; at the sight of my wife, her head would dip and her fingers would suddenly spring to life, rapidly wheeling the chair towards her. My wife never told me what she heard, when she stooped down and pressed her ear to the old lady’s mouth. She’d just smile, firmly gripping the Chinese pear the lady had pressed into her hands. In the evening, once we were home, she’d slide its sweet, juicy flesh into my mouth like a secret, one slice at a time.

As for me, standing behind my wife, all I wanted was to make my presence as unobtrusive as a shadow. With a smile fixed to my face, I carefully remembered the names of all her friends, spoke very little, nodded at the appropriate moments and, every so often, made sure to place morsels of food in her bowl. In this way, it was easy enough to win everyone’s affection.

‘How come you don’t have friends of your own?’ my wife would ask me, and I never had an answer. I had my wife – and later, Lily – and because of my wife I had all her friends, in a way, and this was enough for me. But when she asked the question, my contentment made me doubly ashamed. I didn’t mind not having a social circle of my own. Wasn’t it just further proof that my reclusive character was unsuited for mainstream society? Before my marriage, in an attempt to keep up ‘appropriate’ levels of interaction, I sometimes dragged myself along to the staff socials organised by the factory, or joined my parents on low-cost outings with the local community centre. Afterwards, I was always exhausted, filled with shame and frustration at the thought of my chameleon-like facial expressions, and all the things I’d said but not meant. At the same time, I found it reassuring to have made the effort, as though I’d fulfilled a duty to act like a human being. Once I was married, I attached myself to the goodwill around my wife, like a cold shadow hitched to a warm human body, and found myself winning the approval of others without any struggle at all.

*

The men all lived near the factory, and to reach the city centre they had to endure the torture of the train ride. I’ve already explained what it was like – they liked to stress that, were it not for our great friendship, they would never put themselves through such torment on a day off. But I didn’t believe they would ever have let their dislike for the journey stand in their way. What they declared to be our ‘friendship’ could have been the reason, but there were other possible factors: the exciting buzz of the city, or the table laden with food that my wife prepared for every gathering, accompanied by an endless stream of beer. Perhaps even more to the point, they had bellies chock-full of complaints, and they needed to get far enough away from their own homes to vent in peace.

In the furniture factory, I never went near these men. I worked silently and alone, by a window with a view onto a line of cotton trees. If you walked deeper into the factory, passing through the angry sound of hammers banging against wood and steel, you’d see the irate, exhausted eyes of the men, turned a dull grey by the swirling sawdust. But now, enthusiastically recounting their misfortunes from the comforts of my home, their eyes emitted vivid beams of light. Sometimes, their faces would take on the expressions of dictators, lining up their personal tragedies like obedient citizens. Naturally, they would conclude that their wives were the eyes of every storm, or else their wives’ parents, or those foreigners who kept coming in to find work, or the tropical climate, or the pollen that filled the streets in springtime. If it hadn’t been for them, the men would have been bolder, and lived entirely different lives.

Listening to their endless, meandering talk, it was hard not to let my mind wander. I’d slip away down a little forked alley, walking further and further along, losing myself in my thoughts. In this sense, I had to be thankful for their boorish, oblivious natures, because it meant they were unlikely to notice that my attention was elsewhere. I suspected that even they ended up lost in their own chatter; lost in forests they had planted themselves. Then there’d be a few words that struck them like sharp stones, shocking them back to consciousness. Their faces flushed and their ears went hot, and they worked themselves into such aggressive, emotional states that I felt like a wild animal tamer, with a duty to calm them down. I’d keep their drinks topped up and bring more food from the kitchen.

On this occasion, I brought out the last of the comfort food: the chicken my wife had roasted the previous night. Such a beautiful bird, wings clamped tightly against its glistening body. Its head inclined slightly towards me, with its crest angrily sticking up. The eyes had been shut all morning, but somehow were now wide open and staring fixedly at me, as though sizing me up. I caught sight of my face reflected in the television screen; you couldn’t have called it a warm face, but I watched it crack into a winning smile. This was something I’d learned from experience: a facial expression is like any other domesticated life form, knowing when to nod and wag its tail, or when to burst out laughing.

I was surprised to see this same smile reciprocated on the men’s faces. Usually, they kept up an uninterrupted litany of grumbles and debates, only stopping after a string of reminders that the last train was due. That day, however, they lost interest in talking ahead of schedule, and had no appetite for the food left on the table. But they seemed to have no intention of leaving. I looked away from them, towards the door to the kitchen, thinking of the strip light hanging down at one end, wishing I could go in and fix it. But the men pinned me with their stares. Their silent smiles were like so many nails, keeping my buttocks tacked to my seat. Not knowing what to do, I turned to watch the sky changing colour through the window. At first, a big group of black jellyfish-like creatures seemed to be swimming through it, slowly devouring all other colours, but gradually I realised it was the other way around: the other colours were vomiting the black, and this was why it looked so mottled and fractious. And in front of that ominous roll of blackness, faces were pressing in on me, their hands reaching for my arms, clasping me in a brotherly embrace. One of them patted my back and said, ‘Don’t keep your feelings stuffed in your guts, how are things with the wife lately? If there’s something going on, you should tell us.’ Then he poured the second half of a bottle of beer into my glass, filling it to the brim, and cheerily told me that they weren’t leaving until I confessed the truth.

I took a sip of beer and, as the bubbles dissolved pleasurably in my mouth, wondered whether this was a rite of passage, and they were welcoming me as one of the guys. But all I could do was shake my head, because what could I tell them about my wife? That late every evening, once our kid was in bed, we huddled under the same sheet, tired but happy, discussing the menu for the next day’s dinner? That I liked to go food shopping in the market after work, examining the shape of an aubergine or an onion, contentedly imagining the delicious aroma once it arrived in her hands? That I would bury my head between her thighs and stick out my tongue, tasting her sweet, seaweed flavour? None of those things were suitable for sharing. Not because they were too private, but because they were too close to happiness. Pain and misfortune are the only gifts suitable for friends; only shared tragedy builds friendships. Perhaps because they’d had too much to drink, the men’s eyes glowed red and they encircled me like a pack of starving dogs, eager to gnaw on the bones of my hidden sadness. But what did I have to feed them?

*

There was nothing in my present life that I could really complain about. I couldn’t imagine doing any job other than working in the furniture factory. I loved the scents of the different kinds of wood, and how each had its own distinctive grain – to the point that, every time we shipped out a finished chair or bedframe or, most of all, big wooden farmer’s table, I felt a pang of regret. And my blissfully-happy marriage was surely some mysterious gift of fate, because until I was thirty-eight years old, I’d never even been in love.

It all started with the complimentary ticket to a Christmas party that came attached to my family’s new air conditioner, giving the address as a three-star hotel in the city centre. The moment my father solemnly pressed it into my hand, I knew there was no getting out of this assignment (we weren’t a well-off family and unexpected gifts were bright spots in our lives, certainly not things to be turned down). But when I stepped into the hotel ballroom, which was festooned with streamers and balloons, with my face freshly shaved, dressed in my only white shirt, I immediately regretted that I’d come. I walked into the crowd of men and women I’d never met before, and felt their chatter and laughter weighing against my chest, leaving me unable to breathe. I kept walking straight ahead, my eyes trained on the back of the room, where there was a row of long tables covered in white tablecloths. The tables were laden with all kinds of little delicacies – light glinted off the grease of flaky pastry rolls and the grooves of the fresh cream swirled on top of tiny cakes, and this was my salvation. I marched single-mindedly towards them and piled my plate high. Then, selecting an out-of-the-way corner, I settled into an unoccupied chair and promised myself that I could leave once I had eaten all my food.

I must have been too concentrated on the cakes, because until she whipped out a shiny silver fork, I didn’t notice my wife (although at that stage she was still just some unknown woman). She sat down in front of me and exclaimed: ‘This dessert’s all gone! You don’t mind if I have some of yours, do you?’

As though conducting a symphony, she held her shiny fork poised over the mini donuts on my plate (believe it or not, I’d taken two of every kind). I nodded immediately; I’m sure I blushed. She grinned, revealing a row of widely-spaced teeth. It thrilled me to discover that the gaps between her teeth were much bigger than other people’s; dark and mysterious, like tunnels waiting to be entered.

Her curtains were the gauzy, translucent kind that let light flood in, dispersing the last, muddled dreams of the early morning. I thought she was still in bed, but when I reached for her my fingers clutched at air. I staggered out of the bedroom, calling wildly through the unfamiliar flat, the events of the night before as uncertain as my footsteps. Back then, I didn’t even know her name. I followed the hallway, peering into another room, which led to another room, whose walls seemed to block the way to another. Confused, I walked back along the hall. The woman seemed to have vanished, until her face pressed against my shoulder, appearing as suddenly as a snake darting from a cave. ‘Where have you been hiding?’ I asked, and she smiled but said nothing, curling a hand round to pass me a cup of ink-black coffee and a mini donut dusted with icing sugar.

Her mini donut was much better than the ones in the hotel, just as she had promised. I still remember that morning, and the way we walked out onto the street hand in hand, mouths covered in icing sugar, inviting mockery from passers-by. But I had passed by the kitchen, and there had been no trace of cooking on the gleaming counter tops. I never said anything, but my wife’s ‘disappearance’ wasn’t a one-off occurrence; in her flat, the same thing happened again and again. Was there some kind of secret passage, where she could hide without making any sound? Any time I raised these kinds of questions, she would tap me lightly on the forehead and joke about my over-active imagination.

It’s true that it was just a small, two-bedroom flat. Walking out of the master bedroom, I was confronted by the gloomy hallway. The first room on the right was Lily’s – if I opened the door, I’d see her dolls and wooden building blocks strewn across the floor. To the left was the bathroom, and straight ahead was where we ate dinner every evening, which linked to the living room, which doubled as my wife’s studio. The kitchen was to the left of the living room, and at the back of the kitchen was a door. The door seemed like it must lead somewhere, but when I opened it, all I saw was a headless dressmaker’s mannequin, draped with a coat that hadn’t yet had its sleeves sewn on, a few boxes stuffed with my wife’s yarn and fabrics, stacked on top of one another, and some of her older projects. And if I shoved all this to one side, there was just a murky white wall, pressing in on me.

Before we married, my wife’s flat was like our private express train of snatched pleasures, and I never had the chance to explore it properly. She gave me a tour after I moved in – ‘This used to open out onto an illegal balcony with a view of the street,’ she told me, ‘but it had to be dismantled a few years ago.’ So why did she fail to mention the door? Later, while cleaning the flat, I discovered that, in the hallway, diagonally across from Lily’s room, there was another door; one that I’d never noticed before. It had always been concealed in the shadows, but with the light from Lily’s room spilling into the corridor, I could see its outline. Even in the light, it wasn’t an ordinary door. It looked as though it was afraid and trying to hide itself in the wall, like an enormous creature covered in camouflage. There was no handle and, no matter how I pushed, it wouldn’t budge. I gently stroked the surface, but it refused to respond. The gap between the door and doorframe was too narrow for my fingers to fit.

My wife shook her head when I mentioned it, asking what crazy thing I was talking about now. I brought her over to look but she played it down, saying it was probably just part of the decoration, because a door wouldn’t have anywhere to lead to. Did she think I was some kind of joke? She put her headphones back on, clearly in the middle of listening to something, and burst into hearty laughter. I stared at the black gaps between her teeth, now on full display, but had no way of guessing what they were hiding.

After Lily was born, I often carried her into the hallway and stood in front of the door, pointing at it, saying, ‘Look, Lily, don’t you want to go and play behind the door?’ I would take her hand and try to make her press it into the edges, but she always shook free and threw her arms around my neck, closing her eyes and burying her face in my shoulder. Once, I was firmer about it and forced her fingers into the crack, hoping they’d be able reach past the accumulated dust, but she wailed loudly, as though she’d touched something dangerous. She didn’t stop until my wife ran over, asking what had happened, brow furrowed with concern, and carried her away.

*

Perhaps my wife was right, and the door was just a figment of my imagination. Maybe it was a repeat of another door, one I’d seen in middle school. I had nothing to hide from my wife, but I’d never told her that, once, back then, you could almost have said that I fell in love (possibly, I hadn’t told her because I’d convinced myself I’d forgotten all about it).

Was it the very first day of middle school? I had arrived very early. Because of the sultry weather, or else my aversion to groups, I headed straight for a big, leafy acacia tree. I sat beneath it, enjoying the fresh breeze and imagining my face turning unrecognisable in the shadow, while listening attentively to the voices behind me.

Those two girls must have met before, because they exchanged nicknames and code words that only they could understand, excitedly sharing tales of their fathers being ‘pervy’ – they stretched out the word, making it peeeeervy, as though it had breath and feelings of its own. There was a pattern to their conversation: they took turns to give examples of ‘pervy’ behaviour, and then proceeded to assess it. For example, one girl would tell the other that when her father went downstairs to buy a paper, she’d seen him slipping porn magazines in between the pages. Then the other girl would talk about how her father always took the raised walkways to go home, so that he could ogle the breasts of women below. Sometimes, the fatherly wrongdoings were deemed suitable only for whispers and I couldn’t hear what was said, just the cackles of laughter that followed. After a while, I realised that for them the important thing wasn’t the content of what they were saying, but the exaggerated, mutually-affirming way in which they said it. It brought them closer together.

Once I worked this out, I lost interest and stopped listening. Surveying my surroundings, I saw that the playground had broken up into a series of little cliques. Even the new students had found companions, aside from a few loners who stood off to one side, emanating the wretched air of abandoned animals.

Of course, back then I thought that I was different. For some people, solitude is a choice; for others, it’s something life decides for them. I had actively rejected company, whereas those other students were flawed, and had been squeezed out and abandoned. There was a girl standing by herself, some distance from the other students, grinning in my direction, and I quickly determined that she was one such creature. I had nothing better to do, so looked back at her. A while later, I realised I couldn’t tear my eyes away, and the reason was the wide gaps between her teeth, which made me feel like I knew her. They reminded me of the street market and its row of grinning clowns, lips stretched back so that customers could shoot at their teeth.

When I was younger, there were a few boring streets in District M that would sometimes liven up at night. On the ground, or on makeshift tables, people would lay out random, messy assortments of cheap clothes, toys, household items, and electric appliances. These goods were dusty and dirty, leaving almost no doubt that they were second-hand, but most of the shoppers had no other choice. And thus, despite their sad appearances, the objects still glinted with a desperate kind of life.

For us kids, these rare transformations saw the streets turn into a fairground. A long queue always snaked from the entrance to the space shuttle ride, which charged two dollars to carry children two metres into the air and back again, and crowds clustered around a game of torturing goldfish with a little net. But I only ever had eyes for the wide, flat faces of the clowns. I had an insatiable passion for shooting at their teeth.

Repeated practice meant that my technique was honed to perfection, but even once I could easily have knocked out every single big clown tooth, I always made sure to leave one standing. My father used to accompany me to the market, and refused to let this go; he’d snatch the gun from my hands and shoot out that last tooth himself, winning me the toy bear jackpot but leaving me in tears. He didn’t understand that I couldn’t stand a completely empty mouth, but found a clown with only one tooth left hilarious.

I don’t know why the girl with gaps between her teeth looked at me with such affection, that first day of school. When the scratchy speaker-system voice started repeating orders for us to line up, the clown-girl followed me, and we walked together into the rank of students. Contrary to what I’d first thought, she wasn’t one of the abandoned creatures. As it turned out, she blended easily with all kinds of groups, and was welcomed by everyone. In my case, on the other hand, she was my only friend for the whole of junior high. Perhaps she thought I was the rejected one, and that was why she befriended me? The thought made me want to run away. But then, at lunchtime, when she invited me to sit with her on the old tyres on the school slope, and we traded side dishes from our lunch boxes, my resolve crumbled. And (I have to admit) when she laughed, showing those black gaps between her teeth, I felt indescribably happy.

After class one day, she suddenly asked whether I wanted to come over to hers. She said her mother had bought a lot of chocolate cake the day before, but there was only her at home and she couldn’t finish it by herself. It was the first time I’d ever been invited to a friend’s house. Embarrassed to tell my parents, I crept home to change my clothes, snuck a few pears out of the fridge and into a plastic bag, and then headed out.

The clown-girl lived on top of a hill, in a peaceful little neighbourhood that I’d never been to before, in what turned out to be a three-storey detached house. She came to the door and graciously accepted my bag of unappetising pears. Then, just like a grown-up, she brewed tea for me and served it in proper tea cups, and placed two slices of chocolate cake on two butterfly-patterned dessert plates. Usually, our interactions felt as natural as breathing, but that day, probably because of the unfamiliar surroundings, I felt awkward. For a long time, we sat side by side on the sofa. I was waiting for her to start eating her cake, so that I could follow suit, but she ignored all the refreshments in favour of meaningless chit-chat. I forget what we talked about; all I remember is that she was wearing a silk nightgown that she must have borrowed (stolen) from her mother’s wardrobe. Sitting beside her, every so often I’d glimpse the gentle swell of her still-growing breasts and, whenever she shifted position, feel the heat from her body waft against mine. I don’t know how much time passed before she announced that she was leaving for a bit, but we still hadn’t touched the cake. I watched her walk away and, for several seconds, was unable to react.

I looked up and realised that I was all alone in a spotlessly-clean living room. The ceiling was much higher than the one in my house, and the walls were covered in fragile glass and ceramics. To start with, I barely dared move for fear the house would rock and all those expensive-looking ornaments would come crashing down. But the girl was away a long time and, eventually, I couldn’t sit any longer and found myself walking out of the room. I passed through a room containing a piano and a collection of other musical instruments that I didn’t recognise, and then a room lined with what looked to be very serious books, and then another that was entirely empty aside from a red rug spread across the floor. And then I saw her, on the stairs to the second floor. I followed and remember very clearly that, when I reached the second floor, she was in a hallway not far from me, facing a wall. I called her name, but she didn’t answer. Instead, she vanished. I went to where she’d been standing, and discovered that it wasn’t a wall, it was a door, but there was no keyhole or handle to turn, just a thin seam where the door met the doorframe. I tried to shove it open, but it didn’t budge. Then I shouted for her again, but the house was silent. The door stood defiantly where it was. I gave it a couple of good, hard kicks, but it made no difference at all.

Disheartened, I went back downstairs. I wanted to return to the living room, but suddenly couldn’t remember where it was. I walked all over the house looking, and kept ending up in the room with the red rug. It was like being trapped inside a maze. When I finally made it to the living room, I was pouring with sweat. I went back to where I’d been sitting, and sat without moving a muscle, not daring to drink the tea or touch the cake. There was no clock, so I had no way of knowing how much time had passed, but the little flowers of hazelnut cream on the cake had collapsed, and the rays of sunlight hitting the wall had moved several inches closer to me. When the girl reappeared, I searched her face, convinced that something must have changed, but said nothing. She pointed to my belly and asked what was going on; I looked down, and saw that my trousers were tented like a mountain over my crotch, and my whole body was shaking.

*

I don’t quite know why, but that afternoon I found myself telling my boorish guests all about the door. Afterwards, they looked at me with excited, dream-filled eyes. ‘There’s no such thing as unsolvable!’ they said, telling me that the world’s greatest locksmith was among us.

Giving me no time to think it over or object, the men leapt from their seats. They were like frightened cockroaches, scuttling around the hidden crevices of the flat. The only one I could see was in the hallway, in front of my door (although it hardly qualified as mine). He pressed his nose against it, as if trying to detect its scent. He sniffed up and down all four sides, and then cocked his head and looked thoughtful. Not long after, another man came out of the kitchen with my toolbox. One man – and I have no idea when he’d gone out there – climbed in through the living room window. Another emerged from the bedroom I shared with my wife, hurriedly throwing something on the floor. Surely not the full-length nightgown my wife had been wearing the previous night? Yet another had found Lily’s toy wand and was waving it around. The man in front of the door clapped his hands to get everyone’s attention, and loudly proclaimed his assessment. Without a doubt, most of this speech was just for show, because he added a quiet line right at the end, about only being able to open the door if he had a very fine wire or some other little thing, like a hairpin.

By this stage, the men were gathered in front of the door. What was inside? I watched from a distance, undecided as to whether I wanted them to succeed (not, of course, that I had any real say in the matter). The door looked frailer than usual, like it was barely existing. One of the men poked a piece of very fine wire into the crack, and the door emitted a piercing shriek, as though it wasn’t a door being opened, but a living organism being sliced apart. The whole room broke out in goose pimples.

The door opened. The men were delighted; they lined up and marched single-file into that place I’d never managed to reach. When the last man had disappeared through the door, I was alone in the flat once again. But I was still sitting on my stool. Strangely, I felt no urge to go through the door myself, and instead just stayed where I was. A long while later, I finally walked over. Now the opening was right in front of me, but it was hard to summon the will to enter. The door seemed smaller than it was supposed to be, like it would be impossible to fit through without stooping. What’s more, I’d always assumed it was a standard rectangle, but now that I looked more carefully, it was actually a trapezoid, its sides slanted at bizarre angles. I contorted my body into different shapes, trying to barge my way in, but the door kept forcing me out.

I couldn’t work out how the men had done it. From what I remembered, they’d walked in quite naturally. I tried to shout into the door opening, but the moment my voice passed the doorframe it stopped, as though hitting a muffler. Gusts of icy wind kept blowing in from the other side. I tried to stick my head through, hoping to see something, but the view was blocked by some kind of internal structure (almost as though the door was growing on top of another door).

The mists parted, although I couldn’t say when, revealing a crescent moon like a razored eyebrow on an infinite expanse of face. There was beer spilled on the table, its bubbles all gone, glowing with a soporific blue light. Minutes ticked past and not a single man reemerged from the door. What had they found in there? I thought I could hear a distant shrieking. Would my wife and Lily be asleep by now? I was very tired, and somehow ended up passed out on the sofa.

When I woke up, the sun had restored some reality to the world, including to the roast chicken, which had been stripped of most of its meat. What remained was a wingless, legless, olive-shaped skeleton, with its eyes wearily closed. I went the door, and found it returned to its original state. I traced my fingers along the rim. It was shallow, like a door-shaped shadow, or an imitation of a door. I crooked a finger and rapped with my knuckle, and it made a low, husky noise, like a voice coming from deep in someone’s throat.

*

After the holiday, aside from her prominent suntan, my wife was the same wife she’d been a few days before, and my daughter the same daughter. I shook the box containing the model castle, and Lily shrieked with excitement outside the front door, immediately letting go of my wife’s hand and rushing inside. Without pausing to take off her shoes, she pounced on the box and began tearing it open. At the sight of the fragments of model castle scattered across the floor, my wife gave me a helpless smile, and then announced she’d bought some squid and a bottle of squid ink to make us squid ink risotto for dinner.

The light in the kitchen was fixed, making the plates and bowls in the drying rack sparkle, and my wife looked extremely pleased. At dinnertime, she served us each a plate of the risotto, and placed a big bowl of peach and rocket salad in the centre of the table. As we ate, our mouths turned jet-black. My wife winked, and said: ‘Pretty good to have a couple of days freedom, then?’ Was she hinting at something? I waved the question away, and asked her and Lily about their trip. They looked at one another and smiled but said nothing, as though, inside their inky lips, there was some secret they couldn’t tell me.

Lily lay on the floor by herself, stacking tiny building blocks one on top of the other, completely absorbed in her castle. While my wife was showering, I knelt beside her and whispered, ‘Won’t you tell Daddy what happened while you were away?’ She shook her head, still focused on the construction. I scooped her up and put her on my knees, pressing my face close to hers. ‘First answer your father’s question,’ I said, ‘then you can go back to playing.’ Lily pouted and burst into tears. My wife walked out of the bathroom and took Lily in her arms, kissing her and saying something into her ear, so that the child was all smiles again. How had she done that? She turned to look at me. I expected her to blame me for upsetting Lily, but she just grinned. I saw the gaps between her teeth, black as black, and couldn’t help feeling a stab of resentment.

That evening, I went into the bedroom without waiting for my wife. But before arriving there, I had to pass the unopenable door and, when I did so, I heard a faint breathing sound, like a cry for help.

I wasn’t sleepy, and lay on the bed with my hands behind my head. I thought of how, early the next morning, before the city was awake, I’d have to rejoin the mass of strangers squeezing onto the train. In a city teeming with resentments, who knew what setbacks lay in wait? And in the factory, the air swirling with sawdust, I knew I’d see those men, swaggering past me in their identical windbreakers. I’d lower my gaze and keep on with my work in silence, avoiding their reddened eyes. I loved my work. An advantage to being a carpenter was that you could immerse yourself in voiceless, wordless wood, and a whole day could pass without the need to exchange a single word with anyone.

My wife had not yet come to bed, and Lily had not yet come to kiss me goodnight. I couldn’t sleep, so I got up again. Walking out of the bedroom, I was confronted with the gloomy hallway. The first room on the right was Lily’s – if I opened the door, I’d see her dolls and wooden building blocks strewn across the floor. To the left was the bathroom, and straight ahead was where we ate dinner every evening, which linked to the living room, which doubled as my wife’s studio. The kitchen was to the left of the living room, and at the back of the kitchen was a door. The door seemed like it must lead somewhere, but there was just a murky white wall, pressing in on me. The house was extremely quiet, and I couldn’t find Lily or my wife; it was as though they’d faded into the air. I went back into the hallway and saw the frail door still hiding in the wall, although its outline was blurred. Sitting down with my back against it, I thought I could hear a faint sound coming from the other side. But it could have been the wind rattling a distant window blind, making it chatter like a row of teeth.

Natascha Bruce translates fiction from Chinese. Recent short story translations have appeared in Granta, Words Without Borders, Wasafiri and Asia Literary Review. She was joint-winner of the 2015 Bai Meigui translation competition and recipient of a 2017 PEN Presents translation award. Current book-length projects include Lonely Face by Yeng Pway Ngon (forthcoming from Balestier) and Lake Like A Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (forthcoming from Portobello). She lives in Hong Kong.

Natascha Bruce translates fiction from Chinese. Recent short story translations have appeared in Granta, Words Without Borders, Wasafiri and Asia Literary Review. She was joint-winner of the 2015 Bai Meigui translation competition and recipient of a 2017 PEN Presents translation award. Current book-length projects include Lonely Face by Yeng Pway Ngon (forthcoming from Balestier) and Lake Like A Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (forthcoming from Portobello). She lives in Hong Kong.

Ailsa Liu is an artist working across electronic music, performance, installation, fiction and poetry. Her work can be found in UNSWeetened and Westside Jr. She writes strangely humorous uncomfortable stories, on death and semi-autobiographical experiences, of liminal spaces and their feelings of loneliness and anticipation and anxiety as generative spaces. She is a member of Finishing School and All Girl Electronic. She is currently studying Fine Arts/ Arts at UNSW.

Ailsa Liu is an artist working across electronic music, performance, installation, fiction and poetry. Her work can be found in UNSWeetened and Westside Jr. She writes strangely humorous uncomfortable stories, on death and semi-autobiographical experiences, of liminal spaces and their feelings of loneliness and anticipation and anxiety as generative spaces. She is a member of Finishing School and All Girl Electronic. She is currently studying Fine Arts/ Arts at UNSW. Elizabeth Tan (@ElzbthT) is a West Australian writer and a sessional academic at Curtin University. Her work has appeared in

Elizabeth Tan (@ElzbthT) is a West Australian writer and a sessional academic at Curtin University. Her work has appeared in  Brian Castro is the author of eleven novels, a volume of essays and a poetic cookbook. His novels include the multi award-winning Double-Wolf and Shanghai Dancing. He was the 2014 winner of the Patrick White Award for Literature and the 2018 Mascara Avant-Garde Award for fiction.

Brian Castro is the author of eleven novels, a volume of essays and a poetic cookbook. His novels include the multi award-winning Double-Wolf and Shanghai Dancing. He was the 2014 winner of the Patrick White Award for Literature and the 2018 Mascara Avant-Garde Award for fiction.

Dorothy Tse is the author of four short story collections in Chinese, including So Black and A Dictionary of Two Cities. Her collection, Snow and Shadow, translated by Nicky Harman, was long-listed for The University of Rochester’s 2015 Best Translated Book Award. A recipient of the Hong Kong Biennial Award for Chinese Literature and Taiwan’s Unitas New Fiction Writers’ Award, Tse is a co-founder of the Hong Kong literary magazine Fleurs de lettres.

Dorothy Tse is the author of four short story collections in Chinese, including So Black and A Dictionary of Two Cities. Her collection, Snow and Shadow, translated by Nicky Harman, was long-listed for The University of Rochester’s 2015 Best Translated Book Award. A recipient of the Hong Kong Biennial Award for Chinese Literature and Taiwan’s Unitas New Fiction Writers’ Award, Tse is a co-founder of the Hong Kong literary magazine Fleurs de lettres.  Natascha Bruce translates fiction from Chinese. Recent short story translations have appeared in Granta, Words Without Borders, Wasafiri and Asia Literary Review. She was joint-winner of the 2015 Bai Meigui translation competition and recipient of a 2017 PEN Presents translation award. Current book-length projects include Lonely Face by Yeng Pway Ngon (forthcoming from Balestier) and Lake Like A Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (forthcoming from Portobello). She lives in Hong Kong.

Natascha Bruce translates fiction from Chinese. Recent short story translations have appeared in Granta, Words Without Borders, Wasafiri and Asia Literary Review. She was joint-winner of the 2015 Bai Meigui translation competition and recipient of a 2017 PEN Presents translation award. Current book-length projects include Lonely Face by Yeng Pway Ngon (forthcoming from Balestier) and Lake Like A Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (forthcoming from Portobello). She lives in Hong Kong. Zheng Xiaoqiong (郑小琼) was born in 1980 in Nanchong, Sichuan. In 2001 she left home to work in Dongguan, Guangdong, and began writing poetry. Her poems and essays have appeared in various literary journals, including Poetry (《诗刊》), Flower City (《花城》), and People’s Literature (《人民文学》). She has published over ten collections of poetry, including Women Workers, Jute Hill, Zheng Xiaoqiong Selected Poems, Thoroughbred Plant, Rose Manor. Her work has won numerous awards and been translated into many languages, including German, English, French, Korean, Japanese, Spanish, and Turkish.

Zheng Xiaoqiong (郑小琼) was born in 1980 in Nanchong, Sichuan. In 2001 she left home to work in Dongguan, Guangdong, and began writing poetry. Her poems and essays have appeared in various literary journals, including Poetry (《诗刊》), Flower City (《花城》), and People’s Literature (《人民文学》). She has published over ten collections of poetry, including Women Workers, Jute Hill, Zheng Xiaoqiong Selected Poems, Thoroughbred Plant, Rose Manor. Her work has won numerous awards and been translated into many languages, including German, English, French, Korean, Japanese, Spanish, and Turkish. Isabelle Li is a Chinese Australian writer and translator. She has published in various anthologies and literary journals, including The Best Australian Stories, Southerly, and World Literature in China. Her collection of short stories, A Chinese Affair, was published by Margaret River Press in 2016.

Isabelle Li is a Chinese Australian writer and translator. She has published in various anthologies and literary journals, including The Best Australian Stories, Southerly, and World Literature in China. Her collection of short stories, A Chinese Affair, was published by Margaret River Press in 2016. Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.  Empty Chairs

Empty Chairs

The Stolen Bicycle

The Stolen Bicycle Lunar Inheritance

Lunar Inheritance NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice.

NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice. Middle of the Night

Middle of the Night Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in

Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in  Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu

Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

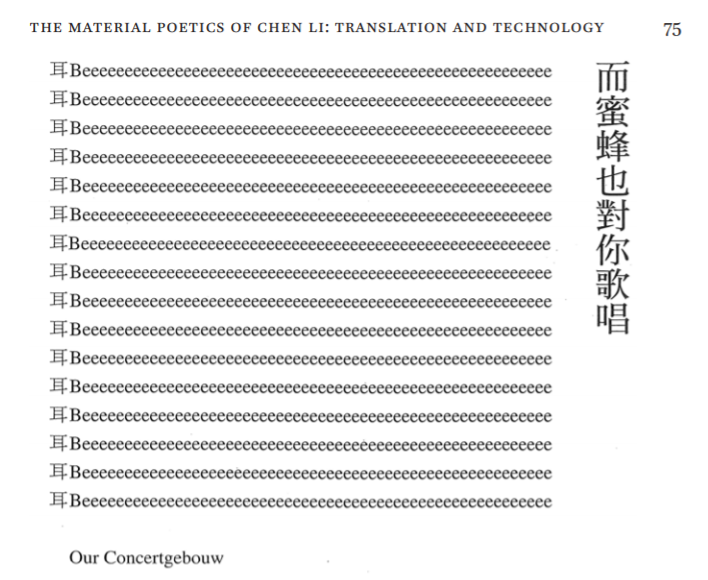

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia.

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia. Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul.

Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul. Encounters with Asian Decolonisation

Encounters with Asian Decolonisation Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people.

Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people. Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China.

Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China. Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty

Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty  Wanling Liu (born 1989, China) completed her MA in Translation and Transcultural Communication at the University of Adelaide. She is a literary translator and teaches translating and interpreting in Adelaide. She has developed a passion for performance poetry and storytelling events and has won spoken word prizes with her poetry published in local anthologies.

Wanling Liu (born 1989, China) completed her MA in Translation and Transcultural Communication at the University of Adelaide. She is a literary translator and teaches translating and interpreting in Adelaide. She has developed a passion for performance poetry and storytelling events and has won spoken word prizes with her poetry published in local anthologies.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia. HC Hsu is author of the short story collection Love Is Sweeter (Lethe) and essay collection Middle of the Night (Deerbrook), which has been nominated for the Housatonic Award, CALA Award and Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Memoir competition winner and The Best American Essays nominee, he has written for Pif, Big Bridge, Iodine, nthposition, 100 Word Story, China Daily News, Epoch Times, Words Without Borders, and many others. He has served as interpreter for the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, and his translation of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo’s biography Steel Gate to Freedom was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015.

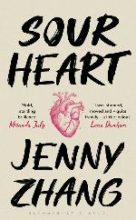

HC Hsu is author of the short story collection Love Is Sweeter (Lethe) and essay collection Middle of the Night (Deerbrook), which has been nominated for the Housatonic Award, CALA Award and Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Memoir competition winner and The Best American Essays nominee, he has written for Pif, Big Bridge, Iodine, nthposition, 100 Word Story, China Daily News, Epoch Times, Words Without Borders, and many others. He has served as interpreter for the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, and his translation of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo’s biography Steel Gate to Freedom was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015. Sour Heart

Sour Heart

Carielyn Tunion aka ALIENCRY is a multidisciplinary artist & serial story peddler with experience in visual arts, illustration, screen production & creative content production. Her focus is on community empowerment through representation, decolonisation practice, and creative collaboration. Her work has appeared in The Experience Magazine, ISMS-zine, Vertigo, 2TheFront Zine. She has exhibited at Lowbrow Denver Pintastic Exhibition, Colorado, Amber Rose’s Slutwalk, LA. This video was part of the SAD N ASIAN group show in New York, and at a @kaleidopress event in 2017.

Carielyn Tunion aka ALIENCRY is a multidisciplinary artist & serial story peddler with experience in visual arts, illustration, screen production & creative content production. Her focus is on community empowerment through representation, decolonisation practice, and creative collaboration. Her work has appeared in The Experience Magazine, ISMS-zine, Vertigo, 2TheFront Zine. She has exhibited at Lowbrow Denver Pintastic Exhibition, Colorado, Amber Rose’s Slutwalk, LA. This video was part of the SAD N ASIAN group show in New York, and at a @kaleidopress event in 2017. Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite,

Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite, Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’

Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’ Billy Sing

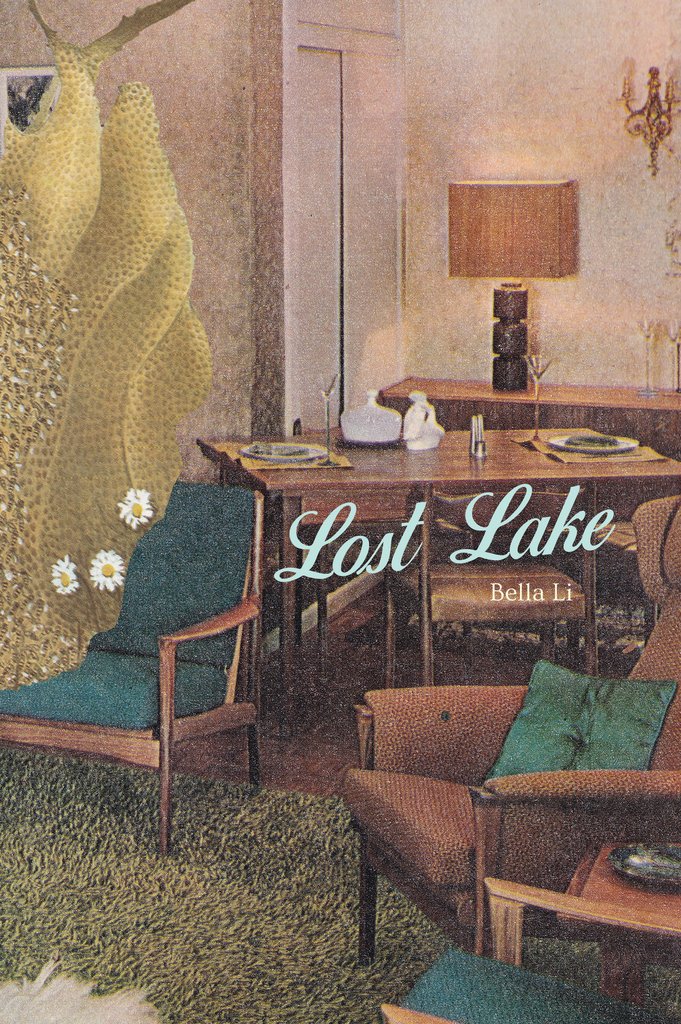

Billy Sing Argosy and Lost Lake

Argosy and Lost Lake

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2 Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of

Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of  Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Emily Yu Zong has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Queensland, where she remains an honorary research fellow. Her doctoral thesis on Asian Australian and Asian American women writers was awarded the 2016 UQ Dean’s Award for Outstanding Higher Degree by Research Theses. Her research interests include ethnic Asian literature, gender and sexuality, and literature and the environment. She has published academic articles, interviews, and book reviews in Journal of Intercultural Studies, JASAL, New Scholar, Mascara Literary Review, and Australian Women’s Book Review.

Emily Yu Zong has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Queensland, where she remains an honorary research fellow. Her doctoral thesis on Asian Australian and Asian American women writers was awarded the 2016 UQ Dean’s Award for Outstanding Higher Degree by Research Theses. Her research interests include ethnic Asian literature, gender and sexuality, and literature and the environment. She has published academic articles, interviews, and book reviews in Journal of Intercultural Studies, JASAL, New Scholar, Mascara Literary Review, and Australian Women’s Book Review. Janet Jiahui Wu is a visual artist and writer of fiction and poetry. She has published in Voiceworks Literary Magazine, Cordite Poetry Review and Rabbit Poetry Journal. She currently resides in Adelaide, South Australia.

Janet Jiahui Wu is a visual artist and writer of fiction and poetry. She has published in Voiceworks Literary Magazine, Cordite Poetry Review and Rabbit Poetry Journal. She currently resides in Adelaide, South Australia. A.J. Carruthers is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from

A.J. Carruthers is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from  Hidden Words Hidden Worlds:

Hidden Words Hidden Worlds: